AircraftProfilePrints.com - Museum Quality Custom Airctaft Profile Prints

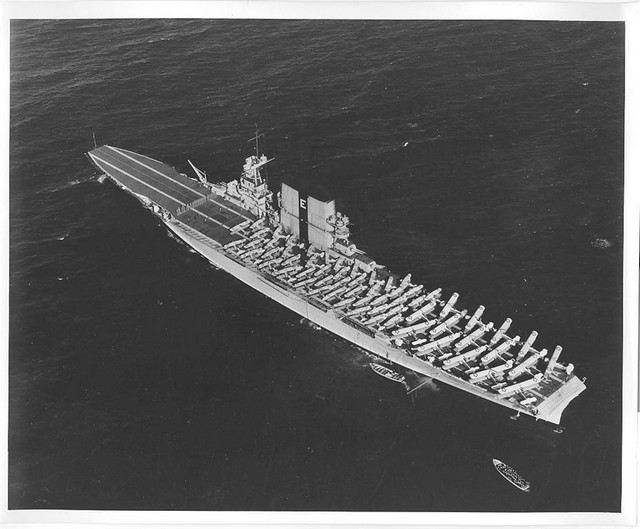

If any adult living in the 1930’s were to be asked what an aircraft carrier was, the image that would most likely come to mind would be that of the American giants, USS Lexington and USS Saratoga, for they undoubtedly had more publicity than any other such ships of their era, staring in a movie (picture1), and providing all the electrical services to a large town for a month! (pictures 2 and 3)(1). In terms of length the were the longest warships in the world (888’ or 282m) and were almost always pictured with their flight decks crowded with aircraft – and as the decks were maroon with yellow lines, and the aircraft sported bright yellow wings – they were among the most colourful warships ever (picture 4). And unlike the USN’s giant airships which were contemporaries and also gained much publicity (a future article will be written about the giant ‘flying aircraft carriers’), Lexington and Saratoga suffered no peacetime catastrophes. What happened on the decks of these two carriers, and in the exercises they undertook, made the United States Navy the leader in naval aviation, a position it has held for over eight decades.

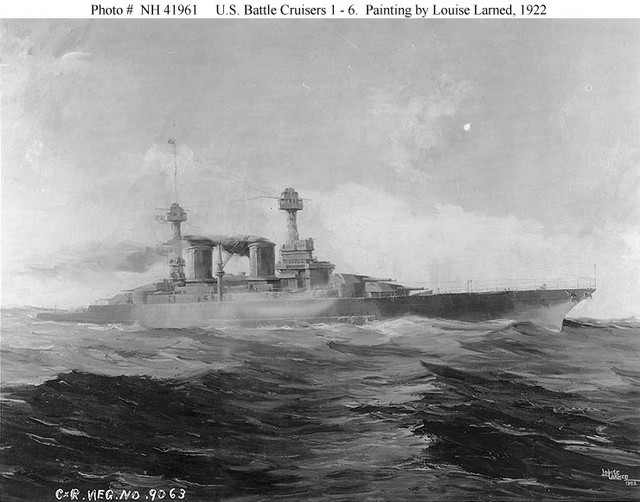

Lexington and Saratoga began as part of a build-up announced by President Woodrow Wilson to build the world’s largest navy.(2) This was done early in 1916, no doubt to show the American voter that the United States would be safe no matter what the insane Europeans, now into their third year of a vicious war, were doing. Keep in mind that the bloodbaths of Verdun and the Somme were only just beginning and Wilson’s announcement was close in time to the Battle of Jutland. In the November, 1916 elections Wilson won on the slogan ‘he kept us out of the war’. Six months later, the United States declared war on Imperial Germany. She had a large navy that was modernizing quickly but the immediate demand was for destroyers and escorts to handle anti-submarine duties, so the six large battle cruisers ordered on Aug. 29, 1916 were put on hold. (3) After the war, still with the goal of having the largest fleet, and being very suspicious of the Japanese, the six authorized battle cruisers were all laid down, but their design had been modified to add 8,000 tons (they would now weigh in at 43,000 tons) and the armament was changed from 10 – 14” guns to 8 – 16” guns. They would be the most powerful ships on earth and among the fastest at 34 kts.(4)(picture 5, above) Naturally, the Japanese indicated they would respond in kind and accelerated their capital ship program (called 8-8 for eight new battleships and eight new battle cruisers); and the British, despite being exhausted and already possessing the world’s largest fleet, indicated that they would initiate construction of four new battle cruisers to be followed by four new battleships.(5) (picture 6) A new arms race, three-way instead of the British-German rivalry before WWI, was breaking out but it was cut short by the new Harding Administration that took over in Washington early in 1921. The American public had turned ‘isolationist’; the Senate refused to ratify the Treaty of Versailles for it would have the United States join the new League of Nations; and the idea of spending money on weapons now that the war was over was seen as pure folly. Thus the Harding Administration invited representatives to Washington in the fall of 1921 to work out a naval arms limitation agreement. The U.S., Britain, Japan, France, and Italy signed the Washington Naval Treaty on Feb. 6, 1922. It set limits on the size of fleets, defined different types of warships in respect to tonnage and armament, set up a mechanism for regular treaty revisions, and even had timetables for the replacement of equipment. In the popular press everyone praised the ‘Battleship Holiday’ – no new construction of capital ships for at least the next ten years. But some exceptions were made. “Largely as a sop to their collective pride the navies concerned were allocated tonnages of aircraft carriers….This was specifically to permit British, American, and Japanese to convert cancelled hulls to avoid unemployment in their shipyards but it provided the excuse to build carriers at a time when funds would have been extremely hard to find”. (6) Carriers themselves were defined as ships with a maximum displacement of 23,000 tons and a maximum armament of 10 – 8”guns; thus the exceptions granted to the United States and Japan to allow battleship/battle cruiser hulls to be converted would result in vessels much larger than any expected to follow. (7) Thus Lexington (CC-1) and Saratoga (CC-3), the most advanced in construction of the six in the class – and presumably the least costly to convert – were chosen to be made into aircraft carriers. Picture 7 shows models in 1922 of what the ships would look like when complete.

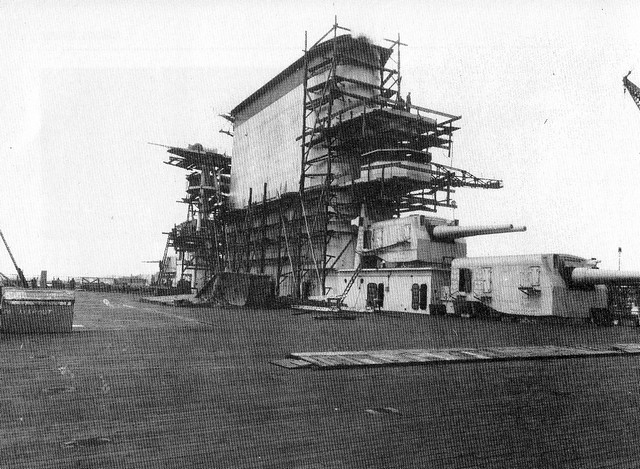

Lexington and Saratoga, notable for their huge size, were also notable for being the most powerful ships in the world. Their power plants were rated at 180,000shp but Lexington developed 209,000shp on her trials and Saratoga 210,000shp. (8) Turbine-electric machinery had been chosen for these ships “mainly because American marine engineering firms at that time were unable to produce reduction gearing of the requisite size and strength for the straight steam turbine power plants for ships requiring such power.”(9) Efficient and rugged, this equipment was heavy, intricate and not easy to maintain, but it was available and had proved itself in the colliers Jupiter and Jason – and Jupiter was now USS Langley. Sixteen oil-fired water-tube boilers drove steam turbines that drove electrical generators: they in turn sent electricity to drive motors attached to the propeller shafts. These shafts were relatively short (119’: 36.6m) and carried 3-bladed props 14’9” (4.5m) in diameter which pushed the slim hulls (fineness ratio of 8) up to 34kts.(10) As with all carriers, the problem of removing combustion gases had to be solved and in the case of the Lexington and Saratoga what was to have been seven (!) funnels when designed as battle cruisers became one huge funnel 104’(32m) long and 79’(24.3m) high, sited 38’ (11.8m) from the ship’s centerline.(picture 8,above) The island was forward of this funnel and sited 41’ from the centerline and all this weight had to be counterbalanced, a problem made even more acute by the placement of the four twin 8”gun turrets on the starboard flight deck, two ahead of the island and two aft of the funnel.(11) (picture 9). These ships required ballast to overcome the inherent list in their design.(12) On July 25, 1921 Captain Robert Stocker, Chief of Preliminary Design, ordered a study of the conversion of one of the battle cruisers into an aircraft carrier. Preliminary carrier designs had become ever larger during 1919-1920 until they were close to the size of the battle cruisers which had just been laid down: as a design exercise, Stocker’s order was timely.(13) Lexington (CC-1) had her keel laid Jan.8, 1921 and was 33% complete when the change to the carrier design was authorized; Saratoga (CC-3) had her keel laid Sept.25, 1920 and was 34.5% complete when taken in hand for conversion to a carrier.(14) When they emerged five years later, they were unlike any other warships on earth, their turbine-electric machinery being only one of their unique features. (picture 10)

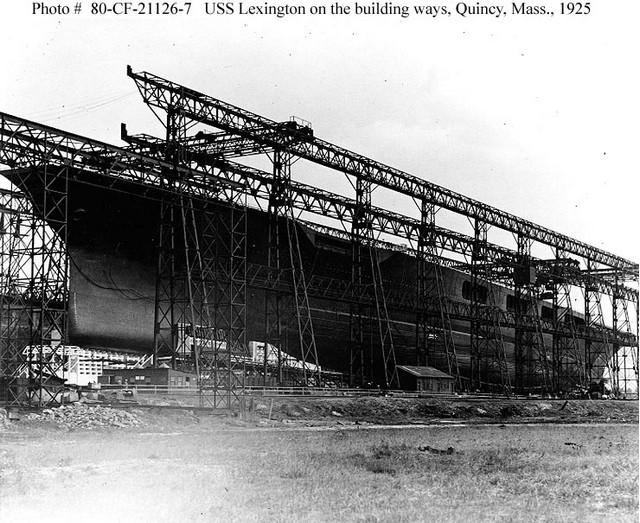

Each of the battle cruisers ordered in 1916 was expected to cost $16.5 million but their late start (laid down 1920-21), change in armament, and the addition of 8,000 tons to the design, undoubtedly would have increased the cost.(15) The conversions to carriers were expected to take three years and cost about $23 million – in the event, and typical of programs involving new technology, the ships took five years to complete. Lexington was built at the Bethlehem Shipyard in Quincy, Massachusetts: commissioned Dec. 14, 1927, she cost $46 million to complete. (pictures 11, above; and 12) Her sister, Saratoga, built at the Camden, New Jersey yards of the New York Shipbuilding Company, was commissioned Nov.16, 1927, and cost $44 million to complete.(16)(picture 13) Both ships displaced an ‘illegal’ 41,000 tons.(17) From the very beginning it was foreseen that these ships were likely to spend their service careers in the Pacific – Bremerton, San Diego, and Pearl Harbour, Hawaii, had docks large enough to service these vessels. “Carriers were the first warships for which the weights of the various components were not the prime determinants of ship size and configuration….In the case of carriers, volume became the dominant issue because the essential components of the ship (gasoline, magazine, hangar space….crew quarters….maintenance shops, and event the aircraft themselves) were all relatively light for their volume.”(18) Even so, the new ships found that space was at a premium. Their hangars (picture 14) were small in relation to other, later, carriers, being 424’ (130.5m), only 74’ (22.8m) wide aft and an even tighter 68’ forward, this narrowness being caused by the hull itself whose beam of 104’ (32m) allowed them to pass through the Panama Canal(19) (picture 15); and by the deep insets along the sides of the hull to house the numerous ship’s boats. Nevertheless, it was 2½ decks high giving 21’ (6.5m) of head room and this allowed numerous aircraft to be partly dismantled and held under the flight deck, a process the Americans called ‘tricing’.(20) This hangar was fully enclosed and an integral part of the hull structure, thus the flight deck was the strength deck (as in British carriers): Lexington and Saratoga would be the only American carriers built this way until the arrival of the Midway class in 1945. The great disadvantage of this design is that aircraft couldn’t be re-fueled or aircraft engines warmed up in this unventilated hangar: these activities had to take place on the flight deck.(21) And getting to that flight deck was facilitated by only two small elevators, the one aft being 30’ x 36’ (9.1m x 11m)(picture 16) and the forward elevator 30’ x 60’ (9.1m x 18.2m) with a 20’ x 26’ section of the flight deck directly behind the aft edge of the forward elevator that could open – split on the centerline and two sides hinged upward, to handle aircraft too long for the elevator (picture 17). Given the numbers of aircraft on these ships (nominally 78 but 90 were often carried: for one cruise in 1930 120 aircraft were carried but 45 of them were dismantled and in crates) (22) the two elevators were very inadequate. After Lexington and Saratoga, all American fleet carriers had more than two elevators. (23) The two ships had enclosed ‘hurricane bows’, a feature not used again on American carriers until the arrival of the Forrestal-class super-carriers (picture 18). The forward edge of the flight deck was only 32’ (9.8m) wide (Lexington’s forward flight deck was widened in 1938; Saratoga’s in 1941).(picture 19) The island and smokestack began as two very ‘clean’ structures but as time went on more and more anti-aircraft guns were added. Carriers have much larger ‘sail’ areas than other warships and this affects their performance while underway and at rest. Lexington and Saratoga had a single 38’ (11.7m) rudder, the largest ever installed on a U.S. warship, but nevertheless, given their long lengths and high speeds, they suffered from a very large tactical radius. They each had three 15-ton anchors at the bow (see picture 18) and when commissioned had four others hung under the flight deck at the stern.(24) And, in keeping with their huge size, these ships had the largest guns ever installed on an American aircraft carrier –four twin 8” turrets (picture 20). As well, they had twelve 5” single barrel guns arranged in groups of three in quadrants just below flight deck level. (see picture 9) In theory, they could duel with anything less powerful than a battleship or a battle cruiser, and had the speed to escape a capital ship’s guns. They had an armour belt 530’(160m) long and 9’4” (2.4m)in depth but it was much thinner than originally planned for these ships as battle cruisers since keeping the displacement as close as possible to 36,000 tons was important. (25)

Operations on USS Langley, particularly under the leadership of Kenneth Whiting and Joseph Reeves, had already established the LSO (Landing Signals Officer) and the use of the deck park and crash-barrier as Standard Operating Procedures for USN naval aviation. As well, dive-bombing and its potential had been demonstrated, and now with the arrival of the Lexington and Saratoga those potentials could be realized. Soon, however, a minor problem revealed itself. Once the two carriers had reported to the Pacific, pilots complained that there was no way to distinguish the two ships apart from the air – landing on the wrong carrier was embarrassing and the tradition soon began of deck crews writing graffiti all over the unfortunate aircraft. The final impetus to do something to distinguish the two sisters was the tremendously embarrassing fact that during one of the phases of Fleet Problem IX (more about this below) Lexington was ‘sunk’ by her own torpedo planes (!) which mistook her for the Saratoga which was part of the opposing fleet during the exercise. (26) Deck numbers were not carried at this time and so ‘LEX’ and ‘SARA’ were painted on the ships’ round-down at the stern (picture 21, above)) and a black horizontal band was painted on Lexington’s stack, and a vertical black band was added on the sides of Saratoga’s funnel.(27)(picture 22). Landing on these ships, despite their size, was a challenge. They were completed with the Mk. 1 arrestor gears designed by Carl Norden: longitudinal wires were part of this system (picture 23) but as an experiment they were removed from Saratoga and the accident rate went down. Nevertheless, the Mark 1 had its problems. “If a plane landed off center, it was inclined to go still further off center. In fact, it wanted to go over the side. Any deviation from the center was aggravated as the plane went up the deck.” (28) Alfred ‘Mel’ Pride, who had designed Langley’s arresting system, was brought back and he designed the Mark 2 system which used hydraulics to stop the aircraft and return the gear to its ready position. This was installed in Lexington, 11 August 1931, and became standard in the USN and by 1933 was being used in British carriers as well. (29) The year 1928 saw the two ships sail towards Florida for work-ups, then the Panama Canal was transited and the two ships had time to cruise to Hawaii before the year was over. The next year saw the three carriers (Langley was included) involved in Fleet Problem IX. Saratoga was to attack the Panama Canal and Lexington and Langley were part of ‘Blue Fleet’ defending the Canal Zone. (picture 24) Saratoga was commanded by Rear Admiral Joseph Reeves, the same “Bull” Reeves who had developed the deck park and crash barrier as captain of the Langley. He soon had 90 aircraft operating from Saratoga’s deck instead of the nominal 72-78. (picture 25). On 25 January, 1929, Saratoga detached from ‘Black Fleet’s’ battle line and with only one light cruiser as an escort, made a high-speed dash south and then north-east: at 3:30 a.m. sixty-nine planes began lifting off Saratoga’s deck 140miles (224km)from the Canal. They arrived at dawn to ‘bomb’ the Panama Canal – to the total surprise of the defenders in the Canal Zone and of the defending fleet.(30) Vice-Admiral Pratt, nominally in charge of the attacking force, later stated “Gentlemen, you have witnessed the most brilliantly conceived and most effectively executed naval operation in our history….I believe that when we learn more of the possibilities of the carrier we will come to an acceptance of Admiral Reeve’s plan which provides for a very powerful and mobile force….the nucleus of which is the carrier.”(31) In other words, the carriers should no longer be tied to the Battle Line and Pratt insisted on future exercises exploring the strike potential of the carrier.(32) Further exercises saw successful surprise attacks on Pearl Harbour in 1932 and 1938 and as a sign that thinking had changed regarding the role of the carrier, the Lexington’s had their large 155’(47.4m) fly-wheel catapult, designed for launching seaplanes, removed in 1934.(33) Pictures 26-28 show Lexington in operation during these years while pictures 29 to 33 are of Saratoga.

In October, 1940, the USN ‘toned down’ – no more yellow wings; no more mahogany stained flight decks (as seen in picture 34, above); instead, a new drabness as can be seen in picture 35 of Lexington just before the Pearl Harbour attack. Lexington shares with IJN Shoho the distinction of being the first of their country’s aircraft carriers sunk by aircraft from another carrier, the Shoho being lost on 7 May, 1942 and the Lexington on the next day. (34) Torpedoes and bombs from the USS Hornet air wing sank the Shoho, one of the opening acts of the Battle of the Coral Sea. Aircraft from IJN Shokaku and her sister Zuikaku damaged Hornet and sank the Lexington while the American carrier’s aircraft damaged, but did not sink, the Japanese carriers. Lexington received two port-side torpedo hits and two small bomb hits and should have survived, but one of the torpedoes had opened a seam in an avgas tank and hours after the Japanese attackers had departed, severe explosions rocked the ship and she had to be abandoned before nightfall.(35)(picture 36) Saratoga had been in San Diego at the time of the Pearl Harbour attack, arriving in Hawaiian waters one week later. She was soon taken out of action by a single torpedo from the Japanese sub I-6 on 11 January, 1942. She was sent to Bremerton for repairs and modifications and thus missed, again by days, the Battle of Midway. Again Saratoga, this time in the Solomon Islands, took a torpedo from a submarine, I-26. Sent yet again to the yards she exchanged her 8”turrets for the twin 5” turrets found on the Essex class (picture 37); had more anti-aircraft guns added; and had new ‘blisters’ in place to compensate for the additional topside weight. In this modernized condition she fought the war until 21 February, 1945 when she fell victim to a kamizake attack. She was hit by three kamikazes and bombs from three other aircraft and fierce fires raged on the deck for the next hour and a half (picture 38): these were brought under control by excellent damage control work but then another attack wave led to another bomb-laden aircraft hitting the forward flight deck. Again, fires were controlled but the forward flight deck was completely demolished, although aircraft could land aft. (picture 39) Only later was it discovered that the ship had taken another hit, likely in the first wave, by torpedo or bomb, at the waterline amidships, but this caused little damage. (36) Again, Saratoga was taken in hand for repairs and emerged with a new forward elevator in the style of an Essex-class carrier but her rear elevator (which was due for replacement back in 1936) was deleted entirely. (picture 40) With only one elevator operations could not be at the same tempo as previously: in late 1944 she had been designated (along with USS Enterprise) as a ‘night-operations carrier’. Now, after returning to the fleet in May, 1945, she was destined to be a training carrier.(picture 41) When the war ended in August, 1945, Saratoga along with dozens of other ships, provided ‘Magic Carpet’ rides for the tens of thousands of U.S. troops returning home to civilian life (pictures 42 and 43).(37) War-weary and obsolete by 1945 standards, Saratoga was one of more than twenty ships anchored in Bikini Atoll in 1946 for atomic bomb tests. Test Able, an air burst, did very little damage (her huge funnel did collapse) but Test Baker, an underwater blast, did what Japanese submarines and aircraft could not do – sink the Saratoga (picture 44).

For the first time in these articles we come upon subjects that have been modeled in every scale and in every possible medium, including card models. And a reminder: I have no affiliation with any of these companies. Neptun produces in metal a 1:1250 scale Lexington (no.131b) as in 1936 and a Saratoga (no.1317) as in 1944. Superior Models produces in pewter a 1:1200 Lexington (no.A513) as in 1942 and a 1944 Saratoga (no.A514). In 1:700 scale plastic, Fujimi has a Lexington (kit FUJ44116: picture 45, above), and a Saratoga (kit FUJ44117: picture 46). Pit-Road also produces a 1:700 plastic kit of Saratoga as she appeared in 1936 (PITW-96: picture 47); apparently, this kit was produced in co-operation with Trumpeter. A photo-etch of WWII parts can be ordered to fit this kit and other 1:700 offerings, from Gold Medal Models (700-32: picture 48). Trumpeter issued their own 1:700 Lexington (1942: kit 0516: picture 49) and 1:700 Saratoga (1930’s: kit 05738: picture 50). The most exciting news of course, was the arrival of 1:350 plastic kits of these famous carriers. Trumpeter out of China produces a 1:350 Lexington as she was in 1942 (TRPO5608; picture 51) and Gold Medal Models has a photo-etch set for this kit (350-33: picture 52). Their Saratoga kit (TRP05607) sees a 1936 rendering (picture 53) and Gold Metal Models has a dedicated PE set for this kit (350-39: picture 54). I will mention, without creating a listing, that extra aircraft are available in 1:700 and 1:50 scales, and even a set of ship’s crew can be found in PE (rather flat) in these scales and a 1:350 set in resin from L’Arsenal (AC350-25 and AC350-33). Going further up the scale ladder one arrives at card modeling. GPM produces a 1:200 card model of Lexington (GPM-0231 – full hull and 1930’s fit) and a 1:200 of Saratoga (GPM-0223 – full hull; WWII fit) and both kits have accessories available. GoMIx-Fly model also makes a 1:200 card Saratoga (Mix-FLM-081: 1930 fit) with some accessories – but it appears this is a waterline model only (picture 55). Taubman Plans Service (see Loyalhanna Dockyard) has 1:96 plans (7 sets for various parts of the ship) for Lexington (presumably ‘as built’ and so will be accurate for Saratoga as well). From the Maryland Silver Company you can purchase USS Lexington Class (CV-2): A Study in Blueprints (11”x 17” soft cover, 184 pages) and you can use these to scratchbuild a model in whatever scale you wish. (38) From the Floating Drydock, plans and hull lines can be obtained in 1:192 or 1:96 scales: different sets are available for different years, beginning with the Lexington in 1929 and ending with Saratoga in 1945. Finally, on the Steel Navy website, Model Gallery, Aircraft Carriers, if one scrolls down almost to the bottom one comes to the link displaying the ‘Lady Lex’ model donated to the National Museum of Naval Aviation in Pensacola, Florida, by Cdr. Josiah ‘Cy’ Kirby, USNR (Ret.). Next: IJN Akagi and Kaga

Endnotes: 1.”In December 1929, Lexington was recruited by the city of Tacoma, Washington, to provide electrical power as the normal hydro-electric source was threatened due to a drought. Such was the power generation capability of these ships that she was able to provide sufficient power to run the city 12 hours a day for 30 days until the crisis had passed. “ Lexington docked at Tacoma on Dec.15, 1929 and supplied 12,000 KW for 12 hours each day for a month until the city’s reservoir had rebuilt its water levels. The Navy charged the city of Tacoma 1 penny per KwH. Tacoma at the time was not connected to any national or regional power grid. Stern, The Lexington Class Carriers, pp.57,59 and Anderson “CV-2 CV-3 Lex and Sara” in Warship International, no.4,1977, p.313 2. Stern, op.cit., p.12 3. For anyone alive in the last half-century, it is almost impossible to imagine the United States not being a major military power. Yet in April, 1917, it had an army less than 1/3 the size of Canada’s and that army’s recent combat experience had been against Mexican banditos, Philipinne guerrillas, and Plains Indians. It took over a year to draft, equip, and give basic training to 1 ½ million men – but almost 100% of their tanks and artillery were British and French and over 90% of their aircraft. 4. Pawlowski, Flat Tops and Fledglings, 5. Stern, op.cit., p.12 The British G-3 design was often referred to as “Super-Hoods”. The Hood was completed but her sisters were not, being cancelled in 1917. Only two of the battlecruisers were actually laid down and none were named, although it was speculated they would repeat the names of the first battlecruisers – Invincible, Indomitable, Inflexible, and Indefatigable. 6. Preston, Aircraft Carriers, p. 35 7. The British had only the slim ‘Baltic cruiser’ hulls to convert, which they did – HMS Furious, Courageous, and Glorious. It is interesting that the definitions that restricted carriers were decided upon when only one operational carrier, HMS Argus, existed on earth. 8. Hood in 1920 mad 151,000 shp on her trials and Queen Mary exceeded 200,000 in 1934. Not until the Iowa-class battleships of 1943 was a more powerful machinery installed in a ship. Anderson, op.cit, p.292 9. The original gears in Yorktown (CV-5) and Enterprise (CV-6) had to be replaced in 1937-38 and Essex (CV-9) had hers rehabbed in place after initial operations gave out a 125-decibel squeal. Anderson, p.311 10. Anderson, p.312; Stern, p.57 11. Anderson, p.300 and p.312 12. Friedman, U.S. Aircraft Carriers: An Illustrated Design History, p.41 13. Ibid., p.44 14. Anderson, p.292 15. Pawlowski, p.25 16. Ibid., p.28 and p.35 17. ‘Illegal’ because the Washington Naval Treaty had specified a maximum displacement of 33,000 tons for these ships (and Japan’s two battleship conversions) with an additional 3,000 ton allowed to ‘modernize’ against air and water attack. 18. Friedman, p. 2 19. The maximum flight deck width was 136’ and portions of the 5”gun galleries were designed to fold upwards. The hulls had a fineness ratio above 8, allowing for 30+ knots to be easily achieved. 20. Anderson, p. 310 21. Stern, p.109 22. Anderson, pp.310-311 23. Friedman, p.110 The Essex and Midway classes had three, before and after modernization; the Forrestals and the supercarriers that followed have four. Interestingly, the new generation, beginning with USS Gerald Ford, CVN-78, will only have three elevators. 24. Anderson, p.309 and Stern, p.41 The bow anchors were stockless and the stern anchors, which were later deleted, were kedge style. 25. Stern, p.25 26. Ibid., p.40 The island and stack were on the starboard side, just as in HMS Hermes and HMS Eagle. The final design of Lexington and Saratoga was established late in 1924 (the armament issue being the final bottleneck) and one reason given for choosing the starboard side for the American ships – besides pilots’ preference – was that from starboard one had a better view of buoy markers in narrow channels 27. Ibid., pp.113-114 28. Ibid., pp.114-115 There were 14 wires for stern landings and six at the bows – U.S. carriers up to and including the Essex class practiced bow landings in case the stern flight deck should be damaged. An Essex-class carrier could make 20 knts full astern: the Lexingtons could do 30 knts. Bow landing practices ended in 1944. One insult begun on the Lexingtons and continuing until all axial-deck carriers were replaced by angled-decks was to call a pilot who caught a late wire a ‘Dilbert’. 29. Idem 30. All sources make reference to this accomplishment but the most detailed account is in “Admiral Joseph Mason ‘Bull’ Reeves “ article by Mark Denger and Norman Marshall in the California Center for Military History. Some sources indicate 71 planes were launched, others 70. 32. Thus the USN was ready to use its carriers independent of the Battle Line when, thanks to Pearl Harbour, the Battle Line ceased to exist, replaced by necessity with carrier-based ‘task forces’. 33. Originally there were to be three of these, but two were deleted from the building plans as a weight-saving measure. 34. Stern, p.93 35. Preston, p.110-113 “[Lexington] continued to burn fiercely until, glowing bright red from end to end, she was sunk by 5 torpedoes from the destroyer Phelps”. 36. Stern, pp.92-94 37. Friedman, p.55 38. This book of blueprints is not cheap, however, listing in 2010 at $75 US ($105 for non-U.S. residents)

“Admiral Joseph Mason “Bull” Reeves” by Mark Denger and Norman Marshall, California Center for Military History “CV-2 CV-3 Lex and Sara” by Richard M. Anderson, in Warship International, no. 4, 1977, pp.291-328 Friedman, Norman, U.S. Aircraft Carriers: An Illustrated Design History, United States Naval Institute, 1983 History of American Aircraft Carries -- video “History of U.S. Aircraft Carriers” in Ships of the World, no.551, 1999 Knott, Richard C., A Heritage of Wings, Naval Institute Press, 1997 Pawlowski, Gareth L., Flat Tops and Fledglings, Castle Books, 1971 Preston, Anthony, Aircraft Carriers, Galahad Books, 1979 Stern, Robert C., The Lexington Class Carriers, Arms and Armour Press, 1993

Main Picture: Naval Historical Center (NHC) NH 82117 Last Picture: www. Pingbosun.net (NH 94899) Picture 1: Movie Poster: Hell Diver 1931 Picture 2: www.navsource.org (NS) 020247 Picture 3: NS 020248 Picture 4: NS 020340 Painting of USS Saratoga (CV-3) underway in the 1930’s made by Michael Donegan for Trumpeter Models Picture 5: NHC NH 41961 -- a painting by Louise Learned, 1922 Picture 6: Craftsman kit: HMS Invincible G-3 battle cruiser design; box art Picture 7: National Archives and Records Administration (NARA) photo # 80-CF-395b Picture 8: NARA – Lexington 1927 Picture 9: NARA – Lexington 1928 Picture 10: Ships of the World, no. 551, 1999, p.24 Picture 11: NARA #80-CF-21126-7 Lexington in 1925 Picture 12: HCC NH 51323 Lexington, final fitting out Picture 13: NS 020352 launching of Saratoga, 1925 Picture 14: NARA Picture 15: NS 020313 Sara in Panama Canal Picture 16: HCC NH51380 Picture 17: NARA -- forward elevator Picture 18: NARA -- Lex in drydock 12 Jan 1928 Picture 19: NARA – Lex with widened forward flight deck Picture 20: NARA – 8” turrets Picture 21: NHC NH 67420 -- Lex, 1936 Picture 22: NS 020205 Picture 23: NARA -- longitudinal wires Picture 24: NS 020210 – all three carriers at Bremerton Picture 25: NARA -- ‘tricing’ in Lex 1934 Picture 26: www.oldairplanepictures.com Picture 27: www.oldairplanepictures.com Picture 28: NARA 80-G-416531 Picture 29: NARA 80-G-651292 Picture 30: NHC NH 75874 Picture 31: NS 020301a --1934 Fleet Review Picture 32: NS 020318 Picture 33: NS 020342 -- Saratoga, incorrect date Picture 34: NS 020369 Picture 35: NARA # 80-G-416362 Picture 36: NHC NH 51382 Picture 37: NARA -- 5” guns; Saratoga Picture 38: NARA -- kamikaze strike on Saratoga Picture 39: NARA – forward deck damage Picture 40: USN -- single elevator—late war Picture 41: NS 020348 Picture 42: NS 020371 Picture 43: USN - Sara’s last configuration Picture 44: NS 020333 Picture 45: Fujimi box art: kit 44132 Picture 46: Fujimi box art: kit 44117 Picture 47: Pit-Road kit 96 display model Picture 48: Gold Medal Models 700-32 Picture 49: Trumpeter box art: 1:700 Lexington Picture 50: Trumpeter box art: 1:700 Saratoga Picture 51: Trumpeter box art: 1:350 Lexington Picture 52: Gold Medal Models 350-33 Picture 53: Trumpeter box art: 1:350 Saratoga Picture 54: Gold Medal Models 350-39 Picture 55: GoMix-Fly box art: Saratoga 1:200

Photos and text © 2011 by Dan Linton May 26, 2011 |